Eline Borch Petersen

Principal Scientist, Denmark

Traditional hearing-aid evaluations focus on speech intelligibility, which falls short of capturing the complexity of real-life conversations.

Factors like turn-taking, non-verbal cues, and background noise all influence communication, making it essential to assess hearing aids in dynamic, everyday settings.

In our research, we recognize that traditional hearing-aid evaluations primarily rely on speech intelligibility tests, which measure word recognition in controlled environments.

However, real-world communication is far more complex, involving turn-taking, participation, backchanneling (e.g., “mmm,” “uh-huh”), as well as gestures and head movement.

Hearing loss often disrupts conversational flow, affecting speech levels, timing, and non-verbal cues.

Background noise further compounds these challenges, making it harder for individuals with hearing impairment to follow and participate in group discussions.

If hearing aids are to support meaningful communication, we need to assess them in realistic conversation scenarios.

Our research aims to develop new evaluation methods for measuring hearing aid benefits in dynamic, real-world conversations.

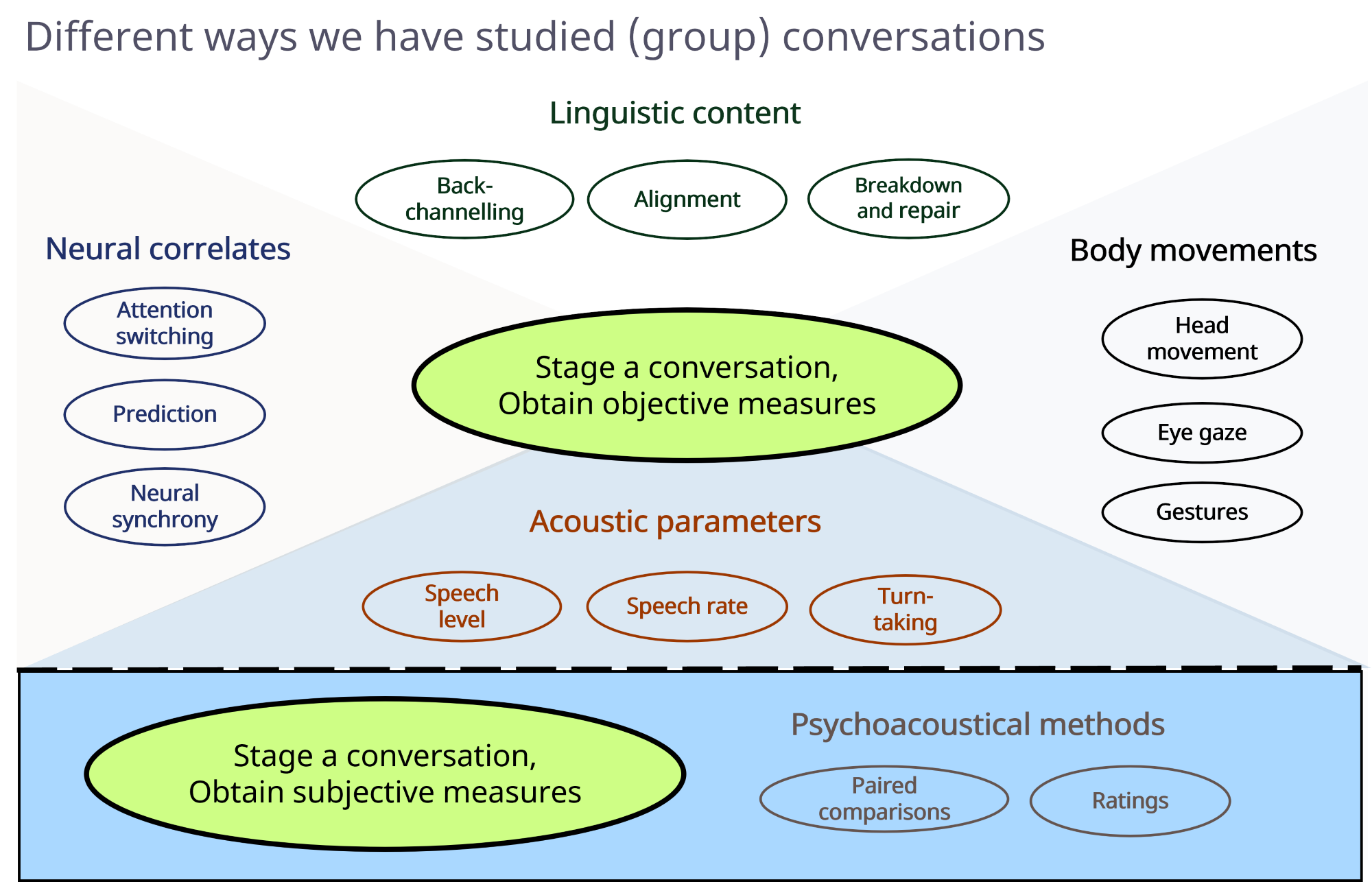

To better capture the complexities of real-life communication, we have taken a multi-method approach:

Stage a (group) conversation and obtain subjective measures

Stage a (group) conversation and obtain objective measures

Across these studies, we have applied different methods for obtaining outcome measures assessing:

By combining these research methods and outcome measures, we have obtained comprehensive knowledge relevant to evaluating hearing-aid benefits.

Our findings highlight how hearing loss, noise, and hearing aids shape conversational behavior:

These results indicate that traditional hearing-aid evaluations do not fully capture real-world conversational success and that new assessment methods are necessary to reflect the demands of everyday communication.

To refine hearing-aid evaluation methods, we aim to:

By shifting from isolated speech recognition tests to real conversational success, our research helps advance:

Improved user experience, making it easier for hearing-aid users to engage in social and group conversations with less effort and frustration.